Vision

Recently, through my visit to the ‘Museum of Ancient Greek Technology’ in Athens, I learned that the industrial revolution almost happened during Ancient Greek times. Unfortunately, due to political and social related events, the industrial revolution got delayed till the 18th century. Nonetheless, the inventions of the Ancient Greeks are marvellous to behold and often rely on a combination of principles from mechanics and hydraulics (e.g. displacement of water and air to rotate gears) to create self-operating clocks, automatic whistling doorbells, but also early robot servants and a magically moving theatre through mechanical pre-programming. I learned that, in those times, there was already an interest and fascination for practical automation, creating an aesthetic experience through “magically” self-operating systems, and how to develop increased complexity into these systems. Behind the curtains operate relatively easy to understand, tangible mechanisms that generate knowledge on natural processes or employ principles as seen in nature for both functional and aesthetic purposes. I find it wonderful that by one museum visit and understanding just a few principles, one can start designing a broad spectrum of tangible systems with accessible materials that have a variety of complexity and output.

Advancements in the fields of artificial intelligence and robotics (amongst others) show the development and societal integration of intelligent and autonomous machines that can do increasingly more and complex tasks. A well-known example is the robot dog of Boston Dynamics, called Spot, which current implementation is mostly in factories to transport objects or check the quality of products. These developments are impressive, however they often rely on a vast amount of training data, complex software and often expensive electronics. Furthermore, the fact that Spot shares physical similarities with dogs supports its integration into human filled factories due to humans’ familiarity with dogs. However, the metal and plastic designed robot does not detect human touch, therefore interactions as those we have with pet dogs do not emerge.

Here lies the question, how do we want to approach further development of these technologies? Which strategies for designing such systems are there and what advantages or new perspectives do they offer? I believe that alternative strategies for the development of intelligent and autonomous systems are necessary to create a platform where knowledge output is distributed, shared and diverse to drive innovation. This means an interplay between niche expertise and accessible methods coming from a broad range of disciplines. Furthermore, I believe innovation should be driven by learning from principles and complex systems as seen in nature and non-human actors as it provides us a broad variety of valuable examples. Innovation should aim to generate knowledge on these natural processes and be aware that imitation of nature is not the purpose but should have meaningful implementation. Last, exploration of both preprogrammed and emerging behaviours should employ methods relating to both functionality and aesthetics to address the full scope of integrating these technologies into society.

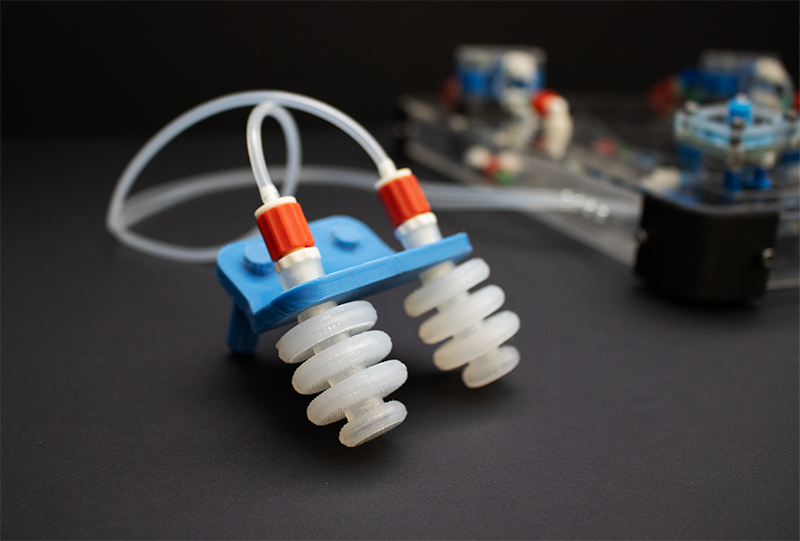

One of those alternative strategies for designing and controlling complex machines are “soft” systems based on physical control. In other words - instead of relying completely on complex software and electronic parts - the earlier mentioned mechanical and hydraulic principles, as applied by the Ancient Greeks, are being implemented to create systems that can do increasingly complex tasks and allow for emerging behaviour through interaction with their environment. One such field where this strategy is implemented is soft robotics. Soft robots are often made of rubber-like – and sometimes “smart” – materials. The compliance of the material allows for adaptability to changing environments and sometimes even to incorporate sensing into the physical body itself. The next step is to not only employ softness in the body, but also in the brain. Again, using these hydraulic and mechanical principles, a system with repetitive, connected moving parts can be designed to automate a soft robot. Utilising nature inspired principles and flexible structures that seem to “magically” operate and explore their environment. I believe the research done within the field of soft robotics is one of the contributors and frontiers to the earlier mentioned platform to drive innovation for intelligent and autonomous systems. Strategies such as the design of “soft” systems contribute to the accessibility, generation of knowledge and interdisciplinarity as I believe innovation of technology should advance towards.

Identity

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing elit. Commodi eligendi fugiat ad cupiditate hic, eum debitis ipsum, quos non mollitia. Commodi suscipit obcaecati et, aperiam quas vero quo, labore tempore.